‘The Brutalist’ navigates the American dream with timeless intrigue

Julia English | Contributing Illustrator

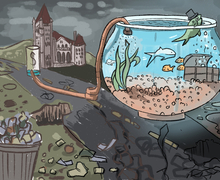

Brady Corbet’s “The Brutalist” follows Hungarian Jewish architect and Holocaust survivor László Tóth as he navigates immigrant life in America. The film is a commentary on societal power dynamics through art and wealth.

Get the latest Syracuse news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe to our newsletter here.

Even in an era of massive comic book films and endless franchises, Hollywood has been looking for the next “great American film.” These stories can span decades, usually have larger run times and are about how one can rise to a place of power in the United States before succumbing to their flaws or corruption.

Stories like Orson Welles’ “Citizen Kane” or Francis Ford Coppola’s first two “Godfather” movies are worthy of this title. The works are featured in the top three of the American Film Institute’s 100 greatest films of all time. But there are also more subversive works, like Paul Thomas Anderson’s “There Will Be Blood” or Spike Lee’s 1992 biopic of Malcolm X, that remain just as relevant then and now as systemic racism and police brutality remain in this country.

Actor-turned-writer-director Brady Corbet tries to add his name to this canon of films with his latest work, “The Brutalist.” The movie has played at the 2024 Venice International Film Festival and has been a darling at other film festivals throughout the fall. With a runtime of about three hours and 35 minutes, including a 15-minute intermission, the film tells the story of a Hungarian Jewish architect and Holocaust survivor László Tóth (Adrien Brody), as he immigrated to the U.S. from the 1940s to the 1980s.

Corbet’s attempt at imitating iconic films may feel obvious and contrived, but “The Brutalist” emerges as a unique and profoundly unsettling drama about our present moment. Corbet is just as interested in America’s place in 2024 as he is in the 1950s and the 1960s.

The film is inherently intertwined with the 20th century and the massive increase in immigration into this country. Corbet crafts an end product that explores art, religion, wealth and power in the U.S. today.

“The Godfather Part II” begins with young Vito Corleone looking at the Statue of Liberty. Corbet pays homage to this intro by showing László stuffed aboard a chaotic boat heading for Staten Island before the camera turns Lady Liberty upside down.

László has escaped a nightmare, still waiting for his wife Erzsébet (Felicity Jones) and niece Zsófia (Raffey Cassidy) to come to America. But now, he must navigate a country that doesn’t fulfill the promises of its American dream.

But sure enough, despite initial struggles like getting banished by his furniture store owning-cousin (Alessandro Nivola) and heroin addiction, he finds his big break with wealthy industrialist Harrison Lee Van Buren Sr. (Guy Pearce).

László, a renowned architect in his home country, brings brutalism to the powerful socialites of eastern Pennsylvania who find beauty in the bland simplicity of Van Buren Sr.’s library. The architectural style emphasizes using raw materials like concrete and steel to create an efficient structure that forgoes any decorative elements.

This leads Van Buren Sr., played with a soulless emptiness by Pearce, to commission László to make a massive community center with a pool, theater, bowling alley, church and much more. The project changes at Van Buren Sr.’s whim and eventually becomes about making a religious center, frustrating his son Harry (Joe Alwyn). László continues the project, opening us up further to his relationship with brutalism and wealth.

In a world where entertainment companies now rely on artificial intelligence, an environmentally harmful tool, “The Brutalist” hints at the sinister implications that efficiency in art can have.

Brutalism also takes on more of a political context because of László’s history. Coming from a war-torn Europe, he uses brutalism to follow young architects of the time who “sought to create structures rooted in functionalism and monumental expression,” according to Architectural Digest.

This massive structure in Pennsylvania highlights a story of religious freedom and success in the U.S. after surviving such horrific atrocities during the Holocaust. The film uses a horns-heavy score by Daniel Blumberg and vast 35mm VistaVision cinematography from Lol Crawley to symbolize the grandiosity of László and Van Buren Sr.’s mission.

Once Erzsébet and Zsófia finally arrive in America due to László’s new friends in high places, it seems that the architect’s home life will be secure, and he can focus on the challenges of building such a monument. If only it were so simple.

László’s relationship with his wife and niece seems transactional and fraught from the beginning. He and Erzsébet argue and there are rarely any moments of actual warmth or love.

Brody, who already has an Oscar-winning performance in “The Pianist” as a Jew during World War II, brings a similar gravity as he did to “The Pianist” while trying to seem like a combative yet principled architect. Jones’ character further reveals an ugliness and destructive nature inside of László. The two actors bounce off each other and create a chemistry based on nastiness and ruthless pragmatism, personified by Jones.

As László struggles to keep the project going, he and Erzsébet receive an opportunity to come to the novel nation of Israel by Zsófia. Even in the U.S., Jewish persecution and memories of the Holocaust are so fresh that Zsófia doesn’t want to stay.

What makes “The Brutalist” such an effective, upsetting work about America comes from the feeling of inevitability swimming underneath the film’s surface. Similar to “There Will Be Blood,” no matter the severe obstacles that the wealthy and powerful face, the wheels of the U.S. and those ruling it will still maintain control.

Corbet posits that the dreams we make about countries or societies will turn out to be dangerous fantasies that the powerful will exploit and perpetuate. Even in an epilogue that takes place four decades after László’s entry into America, these lies will continue to work as a morbid feedback loop with no end in sight.

Published on October 24, 2024 at 12:15 am

Contact Henry: henrywobrien1123@gmail.com